Olympic Complexity

By Chris Davies

The spectacular spectacular with which Danny Boyle opened the Olympics had many things to recommend it. But alongside the dazzle, wit and downright eccentricity of the whole thing, there were two aspects of the opening ceremony that led me to reflect on the complexity of social systems.

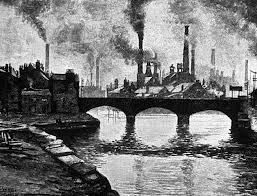

The first was Boyle’s history lesson. By selecting the Industrial and Information Revolutions as punctuation for his story, Boyle picked not only two great moments of British creativity (the former more than the latter, of course), but also two key periods in the complexity of human society.

The first was Boyle’s history lesson. By selecting the Industrial and Information Revolutions as punctuation for his story, Boyle picked not only two great moments of British creativity (the former more than the latter, of course), but also two key periods in the complexity of human society.

By enabling previously inaccessible stores of chemical energy to be harnessed, the Industrial Revolution made possible an explosion in the diversity of production, which in turn made human society dramatically more complex. Broadly speaking, what happened was: cheaper energy led to cheaper production, which facilitated greater diversity, which involved greater complexity; and this catalysed a substantial increase in living standards.

The digital transformation currently sweeping the world, stimulated in part by Tim Berners-Lee’s creation of the World Wide Web, will be similarly far-reaching in its effects; indeed it is already creating major policy challenges, as I described in a previous blog. By reducing to almost nothing a whole swathe of transaction costs, the Information Revolution seems to be giving way to a second great wave of “complexification”. It will do this by allowing us to combine ever greater numbers of components in complex social systems, probably giving way to increased specialisation, and unleashing greater levels of net wealth. As I argued in my previous blog, this is likely to be net beneficial but we should be mindful of the pain involved.

The second aspect of the opening ceremony that spoke to complexity was a subtler one. This was the message that achievement is a collective, systemic phenomenon, not simply the result of one person’s endeavours. This may seem paradoxical in the context of something like sport, which is surely the very acme of individualism: what on earth does Usain Bolt’s ability to run the 100 metres in 9.58 seconds have to do with the broader social system?

The answer lies in some of Boyle’s more eye-catching artistic decisions. The seething, semi-chaotic mass of people who represented industry in the opening 15 minutes; the promotion of the message “This is for everyone” when highlighting the digital era; the reference to a collective system of social support, manifest in the NHS; the use, not of a lone heroic sports star to light the Olympic cauldron, but of seven children. All these moments suggested that collective effort is the thing that will make possible the individual feats of sporting prowess that will be on display during the Olympics.

This is because sport, like so much of the rest of modern life, is about specialisation. Specialisation is possible only thanks to a sustaining network, which is complex and sophisticated. In that regard, professional sportspeople are no different to scientists, artists, doctors, engineers, or any of the other millions of people whose livelihoods depend on being part of a system that is capable of marshalling resources to enable us as a society to specialise. Some may be more talented than others, but as individuals we are only able to exploit our talents if society as a whole works together to allow us to focus on their development.

In that context, it’s no surprise that professional sport developed comparatively recently*. It is only possible to devote the endless hours of practice now necessary to reach Olympic greatness if there is an abundant surplus in the economy, and mechanisms to channel it to you as a specialist. And that surplus is created by all of us.

In that regard, Boyle’s message is a powerful one. For the first time that I can recall, we had an Olympic opening ceremony that said: “Well done for getting here. You are outstanding. But you are able to be outstanding in large part because of those around you.” By shining a light on the collective underpinnings of sport, the ceremony couldn’t have been a better symbol for the power of complexity.

*There were, of course, professional sportspeople in the classical era. They appeared during a time of unprecedented wealth in the Mediterranean, and disappeared once the economy needed to sustain them broke down. As such, their story is consistent with the argument.

In your comment on the collective enabling greater specialization you’ve articulated a seminal point of value from that entrancing event.