“rutenso” – the art of working with complex systems

It’s tempting to think of complex systems as being like simple systems, only more complicated. This is a mistake, of course – complicated systems have many elements but are nonetheless comprehensible in everyday terms. A 747 airliner is hugely complicated, but is designed and engineered to do certain things in certain ways, in a predictable fashion. A complex system, on the other hand, is a fundamentally different class of affair. Feedback loops, positive linking and meshed interconnections mean that however well we think we know where it is now, things will emerge in somehow unexpected and unpredictable ways. And however we interact with the system will affect it – also in unknowable ways.

All this leads to a need for a new way of thinking when dealing with complex systems. It’s counterintuitive to our normal assumptions of how the world works, rather in the same way that led Nobel laureate Richard Feynman to exclaim “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics!”.

As a physicist with a PhD in self-organising systems and for the past 20 years a management consultant bringing a similar lens to people and organisations, I have been grappling with this issue for a long time. When confronted with complexity for the first time, many managers say “Aha, yes, I see…” – and then rush to tackle the issues using their conventional management tools. This is rather like the physicist seeing quantum mechanics and then simply applying their well-trusted (and inappropriate) Newtonian tools, or the naturalist discovering a fundamentally uncontrollable beast and saying “well, once we’ve got it under control we’ll be able to make sense of it”. This is not only the wrong approach, it’s the wrong kind of approach.

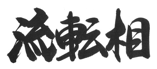

At a senior management masterclass for Tate in London last week, I presented an alternative way of thinking about tackling management and organisational challenges – one which fits with complexity and uses it, rather than fighting it. I have called this ‘rutenso’ – a Japanese word. ‘ruten’ in Japanese means ‘constant change’ (the Japanese having many words for change, much as it is said the Eskimos have for snow). ‘rutenso’ is the art of working with constant change. The characters (beautifully scribed by Shobun Setsu) can also be read in Chinese, where they literally mean ‘flow-turn-image’. My Chinese friends say that this conveys not only working with constant change, but also good fortune coming as a result.

At a senior management masterclass for Tate in London last week, I presented an alternative way of thinking about tackling management and organisational challenges – one which fits with complexity and uses it, rather than fighting it. I have called this ‘rutenso’ – a Japanese word. ‘ruten’ in Japanese means ‘constant change’ (the Japanese having many words for change, much as it is said the Eskimos have for snow). ‘rutenso’ is the art of working with constant change. The characters (beautifully scribed by Shobun Setsu) can also be read in Chinese, where they literally mean ‘flow-turn-image’. My Chinese friends say that this conveys not only working with constant change, but also good fortune coming as a result.

We can contrast a rutenso way of thinking with ‘koteiso’ – working within a fixed frame. Most managers assume that the world works in quite a logical way and that koteiso strategies will therefore work. And they are not completely wrong either. Let’s take a look at the conventional koteiso assumptions about what makes effective organisational change.

- Change is hard and un-natural

- Eliminate difference and uncertainty

- Goals and targets are vital

- Reduce complexity – find the key to unlock the problem

- Huge plans give huge results

- When it’s hard, speed up and act

- Leaders drive and exert

Anyone who has been close to ‘delivery’ over the past two decades will recognise these strategies, and they have been effective up to a point. However, they are all based on a paradigm – a way of thinking about change and how it happens, rooted in simple causal understandings. A target is set. Plans are put in place. Monitoring systems are activated. Everything is focused on turning the handle… and somehow the real goal is lost amongst all the effort and busywork. Target-driven nurses focusing on paperwork instead of patients, that sort of thing.

Can we do better? Yes, we can. A rutenso paradigm – working with complexity rather than fighting it – can give a very different set of ways to effect change. Let’s compare the two:

| koteiso – fixed framework | rutenso – complex framework |

| Change is hard and un-natural | Change is happening all the time |

| Eliminate difference and uncertainty | Difference is inevitable – use it and learning from it |

| Goals and targets are vital | Direction and momentum are vital |

| Reduce complexity – find the key piece | Embrace complexity – there are no magic bullets, look widely |

| Huge plans give huge results | Small actions start things quickly |

| When it’s hard, speed up and act | When it’s hard, slow down and observe |

| Leaders drive and exert | Leaders host and enable |

Let’s look briefly at each element of rutenso:

- Change is happening all the time

This is not a new idea, of course – much of occidental thought is based on this assumption. If change is happening all the time, we don’t need to worry too much about making it happen. Change is not something to be managed and enforced, it’s the natural way of things. The crucial aspect becomes noticing the change that’s already happening – particularly where it is useful, going in the desired direction. It’s tempting and misleading to assume that things are stuck and stable – even if it feels like that.

- Difference is inevitable – use it and learning from it

There is a long and worthy tradition, originating in manufacturing industry, to try to make every product the same – every alarm clock or motor car should be ‘free from defects’. This makes good sense in that particular environment. However, in the complex world of people and interactions, we can start from the other end of the scale – assuming that ‘every case is different’. Even things which ‘should’ be the same are not – quite. For example, think of three meetings of a management team, or three interviews with a benefits claimant. We might think that they are the same, but once we approach with an eye for difference, all kinds of things emerge. The seeds of something may well be lurking in the differences – and if we exclude them from sight, we lose opportunities to influence.

- Direction and momentum are vital

The idea of goals and targets is writ large in modern management methods. However, think about a complex world, where change is happening all the time. Someone once said that ‘goals are dreams with deadlines’ – we set them on day one for achievement on day 365. If change is happening all the time, then it’s difficult to be confident that the same goal will stay valid for the whole year. It may be too easy – in which case sensible ‘satisficing’ managers may back off and focus attention elsewhere. It may become impossibly hard – in which case managers will spend a great deal of time and energy in renegotiation. It may – if you’re very lucky – stay relevant. How often have you seen targets set by government with a fanfare, only for them to be kicking into the long grass later?

A goal is a statement of how far we wish to travel in a certain direction over a certain time. The first thing to think about is not the goal, it’s the direction. Which way do we want to go? Then we can look for momentum – what’s helping us move in that direction already, what progress can we make today and tomorrow? When change is sought, I always look to see ‘what’s the plan for day one’ rather than ‘what’s the target’ – what momentum is visible? Where there’s momentum, there’s progress.

- Embrace complexity – there are no magic bullets, look widely

One key aspect of a complex system is that all the pieces are somehow connected together. As they said on the multi-stranded TV series The Wire, all the pieces matter. If you take one piece out (or change it), then that could well have effects which ripple out and produce widescale impact. Or nothing may happen at all. You don’t know. You can’t know.

Goverments and policy-makers are always tempted to look for the magic bullet – the change which will sort this issue out once and for all. They then look in micro-detail to analyse the situation and seek to find the key to unlock the problem. From a rutenso perspective, this is almost certainly a futile act. However well you analyse the system, you can’t fully understand it. Whatever intervention you make will have unpredictable side-effects – the ‘law of unintended consequences’. Any real-life ‘wicked’ problem will have many aspects, and to get narrowly focused onto one of the them risks missing something important elsewhere.

- Small actions start things quickly

In conventional thinking, big results require big plans. While no-one is disputing the planning efforts of huge projects like the Olympics or the Channel Tunnel, it’s a mistake to think that a big plan is a pre-requisite for success. In a complex system, small actions can and do grow and ripple out – if they are a good fit with the situation. So, trying small experiments to see what happens makes good sense, as does focusing our efforts on the near term (the coming days and weeks) in pursuit of the longer term (the horizon of months or years).

One error that managers often make is to seek (unobtainable) certainty about the mid-term. They mistake ‘having a detailed plan’ for ‘knowing what’s going to happen’. In a complex world, we admit that the future is uncertain, however well we plan for it, and act accordingly. One way to do this is to minimise attention on mid-term and focus our efforts between action today/tomorrow in the right direction. Even the London Olympics was at one point an idea discussed amongst a handful of people!

- When it’s hard, slow down and observe

When things get tough, it’s natural to increase your effort. Push harder! Hit it with a hammer! Run faster! This can be a sensible ploy at first. However, when increased pushing, hitting and running don’t make an impact, it may be time to try something different. Slow down, pause step back. Look at things in a wider framework. Look at your own interactions with the situation. Take a moment to let go, and see what emerges.

The Japanese, amongst others, have a great tradition of taking time out to consider things afresh. They prepare spaces for contemplation, beautifully tended Zen gardens where natural elements like rocks and plants are balanced with man-made raked gravel and pagodas. Of course you don’t have to go all the way to Japan to step back – but it can help to find a different place to do it, and a different person to do it with. New environments can bring fresh thinking with surprising ease.

- Leaders host and enable

It’s becoming increasingly clear that heroic leadership – where the leader knows everything, makes every decision and saves their grateful followers from doom and disaster – is becoming increasingly untenable. In a complex world it’s clearly impossible to know everything – and even if you did, you still wouldn’t know what was going to happen. Various alternatives have been proposed, including Robert Greenleaf’s influential work on leader as servant – in service to their community or organisation. This is a brilliant counterblast to the hero, and yet is not without problems of its own, particularly in corporate settings.

An third possibility is the metaphor of leader as host – both taking clear responsibility and having a key role in tending to their ‘guests’ and nurturing useful interactions within their (carefully created) space. This is a big topic, about which I have written in some detail. You can download a paper and join further discussions of this topic at www.hostleadership.com.

Taken all together, these seven ideas add up to a way of looking at and interacting in a complex world. This is not to say that a koteiso mindset is useless – just that the assumptions underpinning it are not consistent with a complexity viewpoint. See how rutenso might fit for you… Pick one aspect which looks appealing and try it out – with small steps of course!